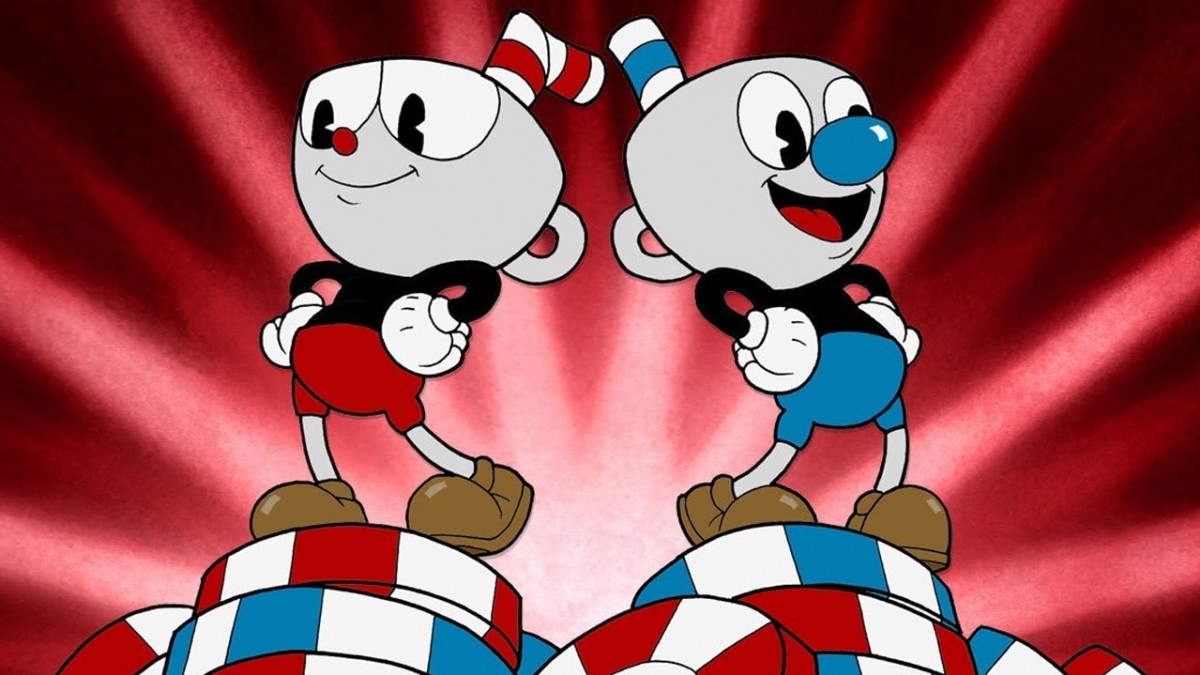

Well, friends, let’s talk about the wonderful Cuphead in our incessant dance! The game has captured the minds and fingers of pianists around the world, mainly due to its two properties: visual and musical irresistibility and extremely high complexity. Cuphead isn’t just stylized as vintage 30s cartoons; it sparkles, hums and dances just like the creations of Max Fleischer and early Walt Disney. His crazy jazz bullet hell requires maximum concentration, patient analysis of the opponent’s patterns and a spinal cord tied into a septal knot. Today, however, I would like to dwell not so much on praising these two merits of the game (although I will inevitably have to slide into the most shameless praise), as on their inextricable interdependence: the complexity of the game is a direct consequence of its irresistibility – and vice versa.

This is how it works.

I have told you many times about the aesthetic dilemma that, for my taste, plagues most AAA games today. The scenery and the characters acting in them have become incredibly rich and oversaturated with details, which is quite natural: the new powers and demands of the player dictate exactly this vector of development of the visual component. But at the same time, it often becomes completely impossible to appreciate such a sophisticated beauty at its true worth: a dynamic scripted scene in Uncharted flies by at lightning speed, and all the splendor, all the delight for the eyes, created over the years in the format of crunches and lack of sleep, remains in the past; it is impossible to fully dive into it. Yes, the rapid pulse of the episode leaves the necessary feeling of being in an action-adventure movie, but after that it becomes a little offensive: both for myself, because I did not have time to consider anything properly (and after all, so much was drawn and built!), And for the developers who all this meticulously painted and built. The Cuphead genre implies even more dynamics, even more rapid movement and a change of scenery. But precisely due to the high complexity and the need to split each boss, each scene many times, by trial and error, discovering vulnerabilities and the correct rhythm, we can breathe in the aesthetics with full breasts, plunge into it entirely.

Many people believe that the high complexity of games is only a dubious way to stretch time, they start to get bored quickly or angrily throw controllers at the wall. It’s not true: a cleverly invented, honest complexity is a fascinating task at the intersection of mathematics, sports and existentiality: to solve it, you need concentration both in the parts of the brain that are at least responsible for analysis, and in the members of the spinal cord, which are responsible for all kinds of motor skills. And in the case of Cuphead, one might say, this is also a task that you solve in a completely delightful environment. Crazy in its own vintage, the world of the game is not just monstrously beautiful: it is stunningly thorough.

To better understand why the game has such a powerful immersiveness, you need to look at how it was born. The Moldenhauer brothers were not looking for easy ways; they understood that in order to recreate the true spirit of the Fleischer era, it was necessary not only to imitate the style, but to work out the very primordial technology, down to the smallest detail. Hand-made frame-by-frame animation, watercolor, modeling and stop motion. Just look at what an incredible work it is:

Chad Moldenhauer, the main artist of the game, speaks of human imperfections as a key point of this approach: it is they, these imperfections, which lie at the heart of traditional animation and make what is happening on the screen so lively and non-mechanistic. As a result, the previously anticipated development period has increased significantly, however, the final product has thus turned out to be something more.